By Raino Isto

Two photographs, taken August 2, 1974, captured Yugoslavian citizens “Trac[ing] the Pathways of the Future,” according to the front-page headline of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia’s principle daily, Nova Makedonija. [1]

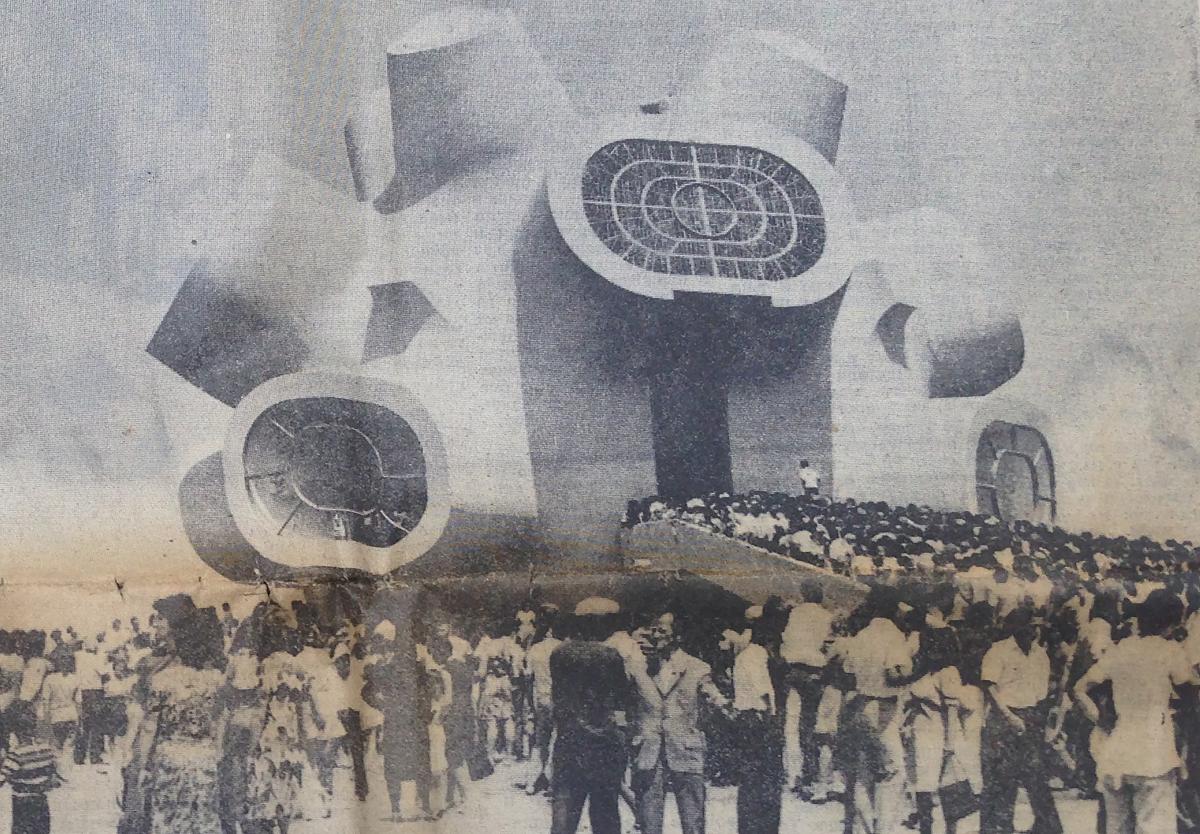

In the first photo, inaugural crowds of visitors gather round the Monument to the National Liberation War and to Ilinden. Through the modernist protruding windows, even more visitors examine the relief sculptures installed in the monument’s four galleries. The caption reads: “The monument... symbolizes the National Awakening, the Ilinden Uprising, the National Liberation War, and Freedom.”

In the first photo, inaugural crowds of visitors gather round the Monument to the National Liberation War and to Ilinden. Through the modernist protruding windows, even more visitors examine the relief sculptures installed in the monument’s four galleries. The caption reads: “The monument... symbolizes the National Awakening, the Ilinden Uprising, the National Liberation War, and Freedom.”

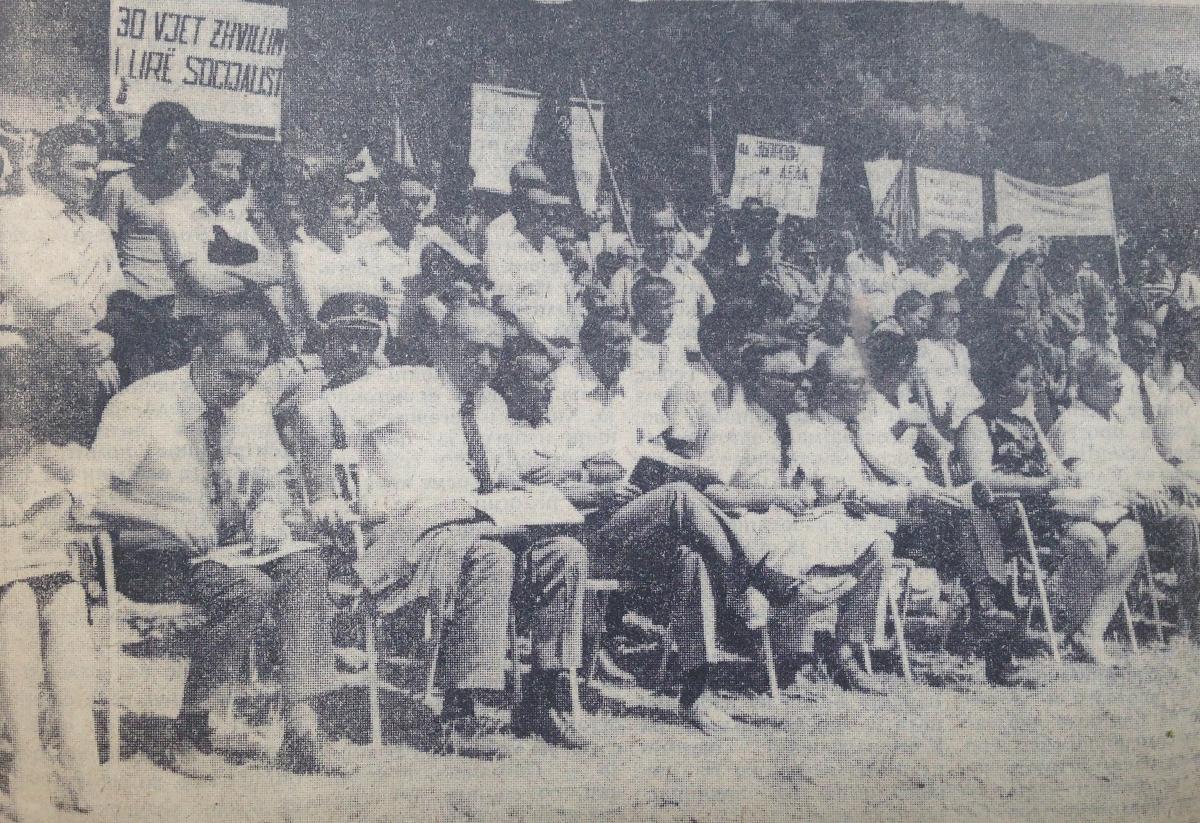

In the second photo, another crowd—some seated, others standing, some carrying banners—gathers in Prohor Pčinjski, in the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Thirty years earlier, ASNOM (the Antifascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia) had met at the same location to proclaim the existence of a Macedonian state, naming Macedonian as its official language. [2] The caption to the photo explained that “10,000 people from Macedonia, Serbia, and Kosovo” attended the anniversary assembly in 1974.

Taken together, these two photographs succinctly illustrate how citizens of Yugoslavia navigated multiethnic histories through an antifascist lens. The Monument to the National Liberation War and to Ilinden was one of the most impressive examples of the narration of these histories through the visual paradigm of socialist modernism. [3] The monument comprises an elaborate memorial complex whose central dome is referred to as the ‘Makedonium,’ designed by the husband-and-wife sculptor-and-architect team of Jordan and Iskra Grabul, with stained-glass windows by painter Borko Lazeski. The white sphere of the monument perches atop Gumenje Hill in Kruševo, the highest-elevation town in Macedonia, and its organic shape and radiating windows present a sharp contrast to the primarily traditional, 19th-century architecture that characterizes most of the town. Inside the monument, a series of reliefs present the history of the Macedonian nation in a visual language of ambiguous curvilinear forms that emerge organically from the walls of the structure: a specific national history narrated through the universal aesthetic of abstraction.

Taken together, these two photographs succinctly illustrate how citizens of Yugoslavia navigated multiethnic histories through an antifascist lens. The Monument to the National Liberation War and to Ilinden was one of the most impressive examples of the narration of these histories through the visual paradigm of socialist modernism. [3] The monument comprises an elaborate memorial complex whose central dome is referred to as the ‘Makedonium,’ designed by the husband-and-wife sculptor-and-architect team of Jordan and Iskra Grabul, with stained-glass windows by painter Borko Lazeski. The white sphere of the monument perches atop Gumenje Hill in Kruševo, the highest-elevation town in Macedonia, and its organic shape and radiating windows present a sharp contrast to the primarily traditional, 19th-century architecture that characterizes most of the town. Inside the monument, a series of reliefs present the history of the Macedonian nation in a visual language of ambiguous curvilinear forms that emerge organically from the walls of the structure: a specific national history narrated through the universal aesthetic of abstraction.

The Makedonium’s formal characteristics were part of socialist Yugoslavia’s attempt to visually distinguish itself from the culture of the Soviet Union, a project that unfolded not only in urban construction projects but also in the building of relatively remote, large-scale monuments commemorating the Partisan antifascist struggle and other historical conflicts. [4] The date of the monument’s inauguration marked the anniversary of the 1903 Ilinden Uprising, an uprising against the Ottoman Empire in the region that resulted in the creation of a short-lived multiethnic independent republic based in Kruševo. [5] The Ottoman forces harshly suppressed the republic after just ten days. [6] August 2—historically celebrated in the region as ‘Ilinden’, or St. Elijah’s Day—thus held a special significance as the day on which Macedonian independence from the Ottoman Empire was perceived to have begun. The ASNOM assembly in 1944 was subsequently hailed as a ‘second Ilinden.’

The multiethnic character of the Ilinden Uprising made it an aptly paradigmatic historical event for the narrative of socialist Yugoslavia’s development. [7] The ASNOM assembly on the anniversary of the Ilinden Uprising linked the history of independence from the Ottoman Empire to the antifascist struggle of the Second World War and established the Ilinden Uprising as a blueprint for unifying the different linguistic and cultural groups that characterized Yugoslavia.

This unity is shown in the second photograph. Among the several banners and signs held by those gathered in Prohor Pčinjski, only one is fully legible in the faded newspaper image, the banner closest to the viewer. It reads “30 Vjet Zhvillim i Lirë Socijalist”—“30 Years of Free Socialist Development”—in Albanian. The choice to highlight the presence of Albanians at the assembly cannot have been accidental; Albanians as a cultural and linguistic group presented a challenge to Yugoslavia’s narrative, since they were not Slavs (and were often Muslim), and the eventual dissolution of Yugoslavia was accompanied by inter-ethnic tensions that continue to persist in Macedonia, Serbia, and Kosovo alike. Thus, the juxtaposition of Albanian participation in the celebration of the antifascist struggle with the universalizing abstraction of the Makedonium shows the effort to present an inclusive, multiethnic history. The socialist present became a point of synthesis, in which layers of history and geography could be brought together despite their diversity, under the aegis of global socialist progress.

The front page of Nova Makedonija tells a story that is markedly different than the ones that proliferate today in the nations that arose out of Yugoslavia’s end. In contemporary Macedonia, the monument is referred to solely as the “Ilinden Monument,” and the role of the antifascist struggle is downplayed significantly. This antifascist legacy links Macedonia to communism, an undesirable association in the era of neoliberal capitalism. Furthermore, the socialist narrative does not suggest the deep, ancient unification of the Macedonian people as an ethno-cultural group, but rather stresses diversity and cooperation between many ethnic groups in the establishment of the modern state. This narrative presents a stark contrast to the current ethno-nationalist discourse in Macedonia and other countries in the region. In the late socialist period, however, there was at least an attempt to use the commemoration of the antifascist struggle—in monuments and public assemblies alike—as a way to chart a unified, multiethnic, leftist state. Despite the failure of this vision in the recent past, there is still much that we can learn from reminding ourselves that it existed and how it was produced.

[1] “Свечености во Крушево и Прохор Пчински: АСНОМ ги трасира патиштата ха иднината,” Нова Македонија August 3, 1974.

[2] The declaration document from the assembly can be viewed here. (last accessed September 8, 2018).

[3] A model of the Makedonium and a few sketches associated with its design are currently exhibited as part of the exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, July 15, 2018–January 13, 2019.

[4] For an overview of socialist modernism in Yugoslavia, see Vladimir Kulić, Maroje Mrduljaš, and Wolfgang Thaler, Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia (Berlin: Jovis, 2012), and Bojana Videkanić, Non-Aligned Modernism: Yugoslavian Art and Culture from 1945–1990 (PhD Diss., York University, 2013).

[5] The primary participants in the uprising were Slavs, Greeks, and Vlachs (also known as Vlahs, a Romance-speaking population who have lived in Southeastern Europe for centuries). Among those Slavs who took part, subsequent interpretations vary as to whether and how many identified as ‘Bulgarian’ or ‘Macedonian,’ as opposed to being unified instead by shared religious identities.

[6] For a thorough examination of the Kruševo and the Ilinden Uprising in the formation of modern Macedonian national identity, see Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003).

[7] This was especially true given the ongoing struggle to integrate Macedonia into this historical narrative, despite its historically peripheral character vis-à-vis Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia, which had formed the core of Yugoslavia in the interwar period. To see the adaptation of the Ilinden Uprising to the context of socialist Yugoslavia’s historiography, see the essays in Boris Višinski, ed., The Epic of Ilinden (Skopje: Macedonian Review, 1973).

About the Author:

Raino Isto is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History and Archaeology and a practicing conceptual artist. His academic research focuses on socialist monumentality in Southeastern Europe and postsocialist artistic engagements with monumental heritage. He blogs and archives at afterart.org.

Raino Isto is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History and Archaeology and a practicing conceptual artist. His academic research focuses on socialist monumentality in Southeastern Europe and postsocialist artistic engagements with monumental heritage. He blogs and archives at afterart.org.