By Anna De Cheke Qualls

By Anna De Cheke Qualls

Rebecca Evans Carroll (’66 EdD) was the first African-American woman to earn a doctorate from the University of Maryland, College Park-–the white institution which in the 1950’s barred her from pursuing graduate study. The University did not admit its first black undergraduate student until 1951.

During segregation, Carroll was forced to do what many African-American scholars did: attend an out-of-state institution that would accept students of color. Carroll ended up at the University of Chicago where she graduated summa cum laude with a master’s in human development and education, under the direction of Robert J. Havighurst and Allison Davis. She returned to UMD for her doctorate in 1962.

“My mother wanted to prove that she could prevail at the University of Maryland that had refused to admit her before. She viewed that denial as a great injustice and she felt vindicated, for herself and other African Americans, when she received her doctorate. She was immensely proud to participate in that commencement,” observes daughter Dr. Constance M. Carroll, Chancellor of the San Diego Community College District.

In her 1996 memoir, Snapshots: The Thoughts and Experiences of an African-American Woman, Carroll describes this event and many other professional and personal successes against the backdrop of a racist society. And yet, through her extensive familial and professional support systems, Carroll had a hugely successful career and personal life.

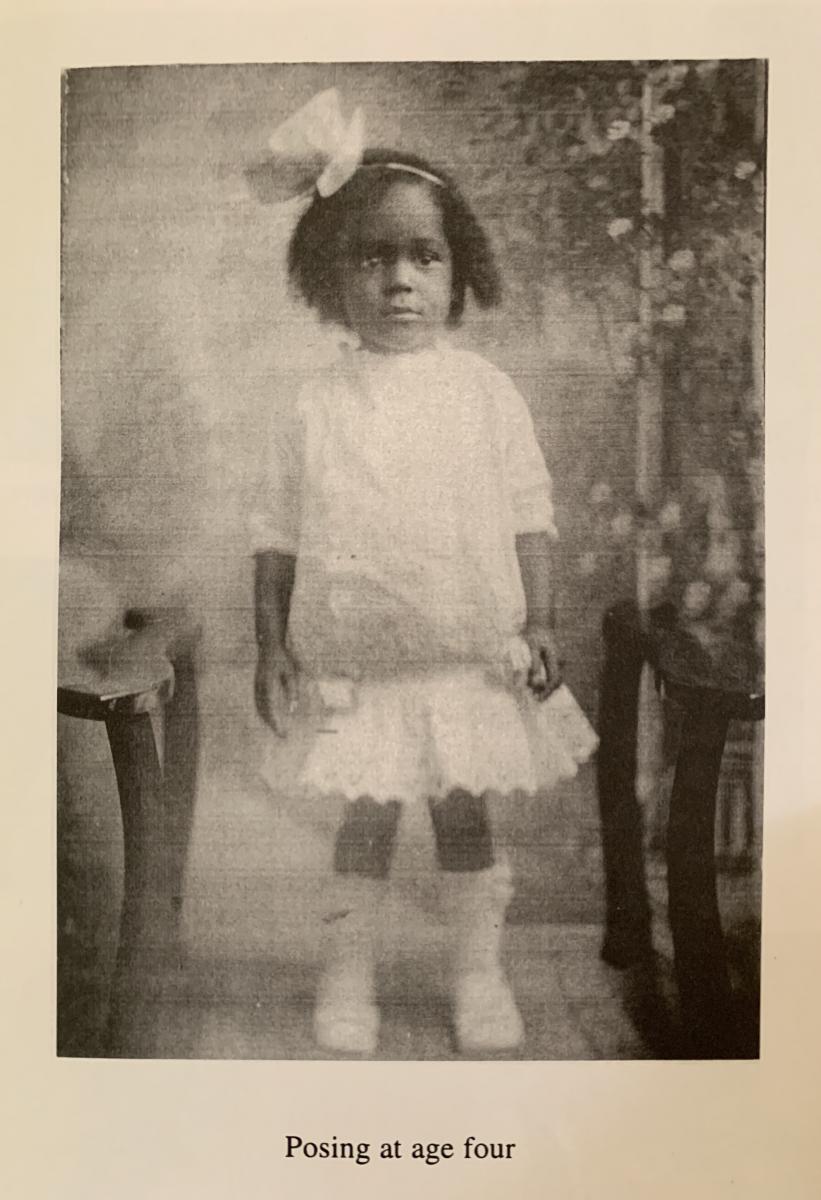

Often called ‘Little Rebecca Evans’ for her small stature, Carroll excelled academically from a young age. At three and a half years of age, she entered first  grade at Saint Barnabas Catholic Elementary School in Baltimore with her older sister Elmira. She was reading by age four, would recite long sonnets in her elementary school years, and played the piano.

grade at Saint Barnabas Catholic Elementary School in Baltimore with her older sister Elmira. She was reading by age four, would recite long sonnets in her elementary school years, and played the piano.

Her parents both believed in the power of education and worked tirelessly to provide for their daughters. Her father Ellsworth, a quiet man, was a laborer at the C & P Telephone Company and her mother Marie, with no more than a sixt grade education, did ‘day’s work.’ Carroll’s two ‘maiden aunts,’ Lillie and Sara, also lived with the family on the 700 Block of Dolphin Street in Baltimore. The children grew up churning ice cream in the summers, shooting fireworks on July 4, and, on Sundays evenings, exploring Eutaw Street’s shop windows.

After ten years in a parochial school with small class sizes, Carroll had to transfer to Frederick Douglass High School in the tenth grade. At age 13, 4’ 10” and 95 pounds, she became a straight ‘A’ student and well respected by her classmates and teachers. She finished valedictorian of her class, and went on to Coppin Normal School to become a teacher. Upon graduation, Carroll took Baltimore City’s teaching eligibility examination, passed with high marks, and in 1936 began to teach on Falls Road. There, Carroll was quickly promoted from being a Class II to a Class I teacher, doubling her salary. With the extra income, Carroll decided to finish her bachelor’s degree at Morgan College (now Morgan State University). She worked during the day, went to school at night, maintained a 4.0 average, and completed her degree in 1942.

Concurrently, Carroll was attending the University of Chicago. Through the ‘Out-of-State Scholarship Program,’ the State of Maryland paid all graduate education expenses for students of color. Candidates were interviewed and subsequently approved for support in the form of tuition, money for books, housing, and travel. Through the program, Carroll was approved for four summers of graduate study. It was in Chicago that she met her husband James Carroll, also an educator. They married in 1943 in the presence of her students from Public School No. 116.

Carroll’s career continued to rise, as a Master Teacher in the district, followed by a promotion to Supervising Teacher. She was responsible for supporting colleagues and student teachers at Coppin through mentoring, weekly lesson plan checks, textbook choices, and observation.

In 1945, the Carrolls had their daughter Constance. When she turned two years old, Carroll returned to work. With two paychecks their new house on Presstman Street could be paid off, and summer travel was suddenly possible. As parents, the Carrolls were able to eventually provide a middle-class home in Morgan Park with music lessons, books, museums, and new experiences-–including trips to South America, Europe, and Asia.

By 1956, Carroll was Vice Principal of Lockerman Elementary School, then Area Director, Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Division, Assistant Superintendent, and finally the first African-American woman Deputy Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction in the Baltimore City Public Schools.

Throughout her life, Carroll was also a fervent Catholic and received the Papal Medal, the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice. As well, she was a leader in the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, and served on various boards throughout her career including Morgan State University’s Board of Regents, the Maryland Public Broadcasting Commission with former UMD Associate Dean Archie Buffkins, the House of Good Shepherd, and the Health and Wellness Council of Central Maryland. She held an additional master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University, and lectured at Morgan State University, Johns Hopkins, Boston College and the University of Tscuba, Japan.

Rebecca Evans Carroll passed away 20 years ago at the age of 81. Time may have passed, and yet her words remain relevant today. The following ‘interview’ with Rebecca Evans Carroll uses excerpts from her memoir.

How did you become an educator?

Growing up in Baltimore as an African-American girl, life was uncluttered with career choices. We had two career choices-–to become a nurse or to become a teacher. The normal schools had progressed in organization and state support from two-year institutions to three-year institutions. Their emphasis was on teacher education. I chose teaching as a career and matriculated at Coppin Normal School, named after the first teacher of her race during post-Civil War days, Fannie Jackson Coppin. I worked hard in the grades that I was assigned for practice: grade five and grade one. My interest in teaching increased when I received an ‘A’ for each practice session. I was told that I was a natural teacher. This compliment and the fact that I became the valedictorian of the graduating class bolstered my self-esteem, and rewarded my family for all the support it had given me. At the end of Coppin, a city examination was given to determine eligibility for teaching in the colored elementary schools of Baltimore. My score on the test was 94.6, a standing of number two on the eligibility list. After commendation, I was given an assignment for grades four to six at a school numbered 158 on Falls Road. In the days of segregation, the 100 schools denoted schools for African-American students. The Falls Road School was a two-room portable school located in the suburban northeast of the city. Discipline problems were to a minimum in the school due to the involvement of the parents, and I must say, the skill of the two teachers in developing a curriculum that was challenging, interesting, and that gave the students opportunities for both success and recognition.

What do you think were the keys to your professional and personal success?

Even after the many years as a professional in the [Baltimore] school system, there is justification for my belief in consistent family support. My positive childhood experiences of yesteryear must be the backdrop for my desire to make a classroom experience for each student interesting, challenging, but, above all, an opportunity for success. If I were to isolate the elements for academic success, I would dip into my own past experiences and list effectiveness in speaking and reading, excellence in mathematics, efficiency in study habits, and enjoyment of learning. Managerial ability coupled with love for people and sincere effort to help each person to succeed must be added to the picture. As well, an integral part of achievement was the mirror of excellence held up for me by my family. Over the years the reflection has indeed become habit-forming.

When people discuss support for children so that they will have wholesome values, the role of the community is often omitted. One thing that I profited from was the help of skilled community leaders. Lillie Mae Jackson and her daughter Juanita Mitchell were two outstanding community leaders. My sister and I both belonged to the City-Wide Young Peoples Forum, run by Lillie Mae Jackson. This organization provided role models for me, enhanced my social and academic skills, and illustrated the power of effective leadership.

As well, love for children, students, and the teaching/learning process seemed to invade my total being and consume most of my time. I found myself constantly reading, studying, and putting into action self-improvement strategies for myself as a professional educator. The result of this foray was a series of promotions with higher educational status and more pay.

What is your philosophy of educating today’s youth?

Family and schools must improve and can improve by discovering, nourishing, and building upon the strengths of the individuals served. All educational planning must be based on the documentable achievement desired for each student. Non-debatable is the fact that positive, supportive relationships in an individual’s intimate life space can serve as a buffer against poverty and can be the catalysts for increasing the momentum of individual achievement leading to educational excellence. My interest in student success in piqued by what I know academic success has done for me. The theory of mastery learning is educationally economic and sound because its aim is success in learning. In this regard, students need teachers and administrators who are imbued with the zeal of furthering, facilitating and promoting high achievement in each. Needless to say, the task is a challenging one and one does and will consume time, organization and teaching strategy, but it’s a task worth all the human and financial cost effort.

From a philosophical/physiological stance, may I share the reality that all humans have a common destiny. We are more alike than different. The accident of birth or the involvement in a societal system does not alter the human’s physiological reality. Our frailty of thought, our institution of formalized education may have caused us to differentiate unduly our educational expectations of individuals, especially at the early childhood level. Subconsciously, the race or economic status of the learner may have gotten in the way. We may have contributed unknowingly in our teaching to the erosion of the dignity of some humans. I believe a new approach is the moral imperative of the day.

Education for the very young is a technique of breaking the cycle of disadvantage. Support for the African-American family must include advocacy and pressure for effective pre-schools, day care, pre-kindergartens, and kindergartens. Involvement from the social, political, and financial point of view is strategic. Networking, coalition of effort, lobbying, are the constructs to be activated.

The black child is a priceless human being in society. Strategic elements in educating the black child are: the organization, which makes the local school more accountable for student achievement, the curriculum, which infuses Africa and African-American content in all school studies-– aiming for true multiculturalism without hierarchy, the teachers who are profoundly interested in growth and challenging each student, and the administration that focuses on maximum individual achievement because all children can learn. Americans must not fail the African-American child because there is increasing need for careful thinking of informed citizens of all ethnic groups.

What underlies issues of race?

Segregation and discrimination really perplexed me when I got older. I really didn’t understand why just our color made the difference. My knowledge of segregation and discrimination became more copious as I studied history and sociology in college. When I went to the University of Chicago, I was enriched by a white professor who seemed to enjoy discussing the problems inherent in our democratic society. She even had us develop a project entitled ‘Separate and Unequal.’ Different committees researched housing, education, health maintenance, recreation, employment, commerce and sales, sanitation, welfare and cultural awareness. Our findings let us to understand that all of us who were black had been victimized, and the whites too. The cancer for the blacks was the development of low self-esteem, while for the whites the erroneous belief in white supremacy. The textbooks, the media, government and even the church did nothing to remove these odious beliefs or state of affairs. Segregation, discrimination, and blatant racism existed because the ethos of the people was suffocated with the rotten stench of belief in white supremacy. Now the stench is all pervasive, and has been disguised with the perfume of democratic capitalism. The suffering is still prevalent in this country, and all over the world. What a cultural waste.

Therefore, we who are African-Americans should be extremely concerned about education. Still permeating American life, since the abolishment of slavery and bondage, is the odious practice of racism that is institutionalized in many instances, and that subtly wreaks havoc on black people. Through the national sins of omission or sins of commission, African-Americans are often made to feel incompetent and inferior. In order to survive the environmental quagmire that results, effective education is needed.

The nation itself benefits by having African-Americans with skills, and with equal opportunity for effective economic development. Intelligent, participating citizens who contribute to their home, community and nation are indeed assets. Persons who are life-long learners, discriminating thinkers and who use their talents and their skills to help others are additional sources of progress for the race. The nation must be willing to pay for quality education today and beyond. Its national budget must place education on par with or above defense.

What is the role of the family in education?

The racist society that controls the racist media continues to create psychological and emotional prisons for all black people. Moreover, black people themselves seldom ponder and capitalize on the strengths of the black family, because what is held up as a giant mirror is a constant, over-exposure on family weaknesses. We are programmed and brainwashed on racial deficits, not the strengths of the black race. We respond to illusions of white supremacy in reference to wisdom, beauty, stability, morality, and excellence by European cultural norms. In sum, both overt and covert racism mirror back to blacks in 1984 instability and inferiority--leading both blacks as well as whites toward warped psyches with deeply negative ingrained feelings.

Since slavery, or the century and a quarter after, our nation has never demonstrated a positive ‘track record’ in terms of legal support of the black family. But, as God would have it, no other family group in our nation’s history has survived the innumerable obstacles, manifested such impressive strengths and made such phenomenal progress in just 120 years.

Today, anyone who is interested in the improvement of society must look to the survival and well-being of the family as a key societal unit. An individual’s social, physical, mental and emotional status is often traced to the family. Moreover, it is through the internal support existing in the family that the self-concept, the self-esteem index, the mental health status and the achievement motivation are conditioned. Asa Hilliard writes that the healthy African-American family is the family that has been able to maintain its connection to history and culture.

Internal support is essential regardless of the family structure--nuclear, single-parent, or extended. It may take the form of listening, discussing or sharing resources. Not all families in Africa had the same structure; however, there were certain basic similarities. Whether or not the unit was monogamous or polygamous, there was always a helpful network of extended kin. The organization of kin contributed greatly to the family’s economic and social stability. The bonds developed in the family can support individuals, thus making it possible for them to be poor but not in an impoverished milieu--to possess happiness that comes from love rather than happiness that comes only from material possessions.

What does being African-American mean to you?

A most profound change in my philosophy occurred when I became steeped in history and philosophy, which redounded in Afrocentricity. Here I am, a self-ordained scholar, realizing the gaps and the odious misinformation in my own education. This realization led me to become an activist in regard to African-American affairs, even making singular contributions to modify my religious heritage. I can understand now my developed centeredness which Molefi Asante describes so poignantly in ‘Afrocentricity.’ When I studied Chiek Anta Diop and Chancellor Williams, my very being rejoiced. I’d found facts that I did not know, despite my doctorate in social science. I found facts that raised my esteem of my heritage. I ask myself now: why is cultural hegemony preserved when there is so much need for diverse groups to work together?

I can now understand the frustration of a William E. Burghardt Du Bois, a James Farmer, and a Malcolm X. I’ve learned to admire men and women who extol their African heritage. I feel negative about education sponsored by a school system that I was part of. Under political domination, it continues to slumber on, separating the heritage of the students, and omitting from the curriculum the African heritage or the heritage of other ethnic groups in realistic terms. The students and their parents are goaded by television, blinded by crass materialism, and impelled by low self-esteem. I believe there has to be another revolution to raise the ghettoized mentality of many of my people who are victims of racism. There needs to develop a sustaining racial pride and practice for blacks.

The heterogeneous public schools do not have the time or are not the places for in-depth analyses of Africa of the past or the feats of African-American leaders. Communities and churches must fill the void. There were 320 patents for inventions registered by African-Americans between the years 1871 and 1900. Probably neither teachers nor students can name the inventors.

I do wish that in this great country of mine-–the richest in the world-–the systems invented to preserve capitalism and democracy would ‘let my people go.’ African-Americans still need social and economic enfranchisement, and it is later than we think.

How did you manage being a working mother?

When Constance was two years old, I returned to my teaching assignment. Fortunately for me, my mother and my sister took turns as the babysitter.’ I hated to leave my baby, but Jimmy [Carroll’s husband] and I agreed that I would return to work. Was the house on Presstman Street bought? This could be done with much more security and much faster with two paychecks instead of one. We both agreed our emphasis would be on spending quality time with Constance rather than quantity time. The morning walks of father and daughter with conversation and vocabulary development and love continued. The evening activity with reading, idea development, and love involving mother and daughter began. The new routine now, however, included our professional preparation for our paid education careers as well as carefully planned weekend and after-work experiences with Constance. The blessing was that my mother and sister added continuity to ou

What are your views on poverty?

I was poor but I didn’t know it. Perhaps this unknowing stance was due to communication. There weren’t enough commercials on the media or feature articles in the newspaper to dramatize for me the fact that in the world there were ‘haves’ and I was one of the ‘have-nots.’ I don’t believe I ever used the word ‘ghetto’ to indicate where I lived. I never used a reference to make comparisons to lead me to believe I lived in community that was not as privileged as others. All I knew and realized was that I was the beneficiary of solicitous, extended family and community support. I basked in the attention given me by loyal members of Saint Pius V Catholic Church. I thrived on the love of my immediate family. No wonder progress seemed so available to me.

Money counts but more importantly for academic success are the human interactions, which can be manufactured in the individual’s best interest. Non-debatable is the fact that positive, supportive relationships in an individual’s intimate life space can serve as a buffer against poverty and can be catalysts for increasing the momentum of individual achievement leading to educational excellence.

These days there is a lot of emphasis on STEM. What is the place of a liberal arts education?

It is important to debunk the myth that liberal arts graduates do not have a chance in the ‘market place’ as compared to graduates with science and business training. I agree with Emile Milne in the February 1980 issue of Black Enterprise, when he states that liberal arts should and can represent a well-rounded education. Students must make this so; faculty must make this so. Milne challenges students to uncover their hidden skills-–these unique skills needed in society today. The challenges for instructors is for personal example and programs of excellence. Milne goes on to list the strengths of liberal arts graduates, namely: adaptability, problem-solving ability, knowledge of the dynamics of interpersonal relations. Persons in sales, marketing, advertising, management have often come through liberal arts colleges. Wilma Brady, a person with outstanding knowledge of the corporate world states, “What gets over best are good writing and verbal skills.” This means engaging in wide reading, choosing friends carefully, getting involved in activities that are broadening, informative, and that provide opportunities for personal development.

We need persons with broad, rich backgrounds of information, with self-developed skills, with courage. Dynamic leadership is needed. Students and faculty need skill, creativity, personal integrity, the will and the stamina to concentrate on those areas of knowledge that can be used to improve the family, the community and the nation. Liberal arts education can be a labor of societal contribution, humanism and love. It must also be rigorous and challenging. Its dispensers, who are the university faculty, must be epitomes of excellence, and concern for the maximum development of each student. The student must be untiring in study, service and the pursuit of personal development.

What advice or charge do you have for young people?

You must discover your role in:

- Advancing the cause of human rights while helping to keep our country as it struggles with interdependence and world leadership.

- Relating positively and productively to the many cultural differences that surround us.

- Curtailing world terrorism and all forms of violence.

- Organizing new coalitions to help us move faster and faster and further in the more effective use of human resources-–as we stamp out the evils of racism, sexism, elitism, selfish competition, callous disregard for the disadvantaged and the poor. You can help rid your community of bigotry by speaking out against it and by not modeling it yourself.

- Even though our resources have been used to abundance, we need you to speak out for conservation-–to move us from helpless dependence upon old forms of energy to the new and greater forms-–wider scientific use of the sun (solar energy), and the wind.

- You (with degrees in business) have the power to discover new formulas for economic recovery, to stem inflation, to decrease unemployment, to form business/labor teams, to develop corporate/social responsibility, to foster greater business/government cooperation, to respond to the needs and well-being of the average citizen. You can make the world ethic noble and uplifting.

- You must be concerned with the health and social progress of our communities.

The torch of courage should enable you first to decide on your own beliefs that are the background of your actions. One must have positive relationships with people, but have the courage to live by one’s convictions, and not follow the crowd.

What does it mean to be a true educator and a professional?

Open the mind toward innovation and changes in education.

- Need for constant study.

- Need for teamwork.

- Need to involve parents from the inception of the new idea (reading English as a second language, black history).

- Need to remove the autocratic stance of the school

Abandonment of old educational myths.

- Learning only comes from the teacher. Children learn from each other when they develop poise and self-esteem from the total environment to which they have been exposed.

- Learning must be based on difficult work.

- The learning problems encountered only lie solely within the child.

Concentration on (human) relationships. It means avoiding stereotype actions directed toward the slow learner, the questioning child, and providing daily activities to develop self-esteem.

- Evaluation of ourselves as educators.

- Do we talk unnececessarily? What are our values? Is our concentration on the activity rather than on the child? What brings us self-fulfillment? Are we truly committed to education? Are we friendly and open to new experiences?

What do you hope for the future?

Perhaps a more incisive kind of accountability for each classroom, each school, each school system will, in the future, be the more precise analysis of the educational growth and even later achievements of the students, even specifying the effective intellectual and social behavior observed. Perhaps greater focus will be placed on the humanistic elements of personal interaction in the family and in the school. No person or community should be exempt from the process.

When we’re really interested, we’ll leave no stone unturned. So we have to be interested--more than just the usual. Each of us is like the tip of the iceberg. There’s more to us than what we realize. We have talents that we haven’t begun to use. Everyone--young and old, well and sick-- can do more to bring about change than she/he is currently doing.

(Title photo of Rebecca E. Carroll: Used by permission of the Baltimore Sun/Copyright Notice: Baltimore Sun, 1982)

(Other photo and text credits: Used by permission of Dr. Constance M. Carroll from Snapshots: The Thoughts and Experiences of an African-American Woman/Fairfax Publishers/1996)